- Elizabeth House

- Jan 21, 2022

- 1 min read

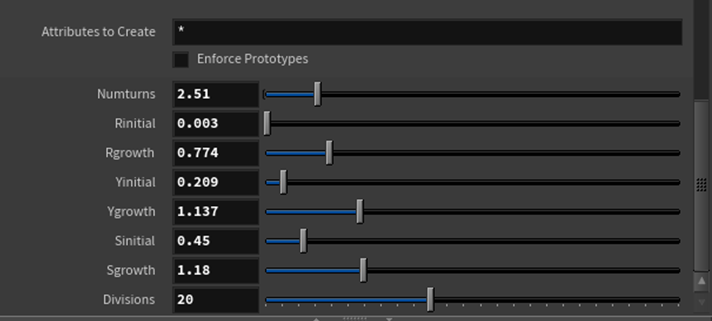

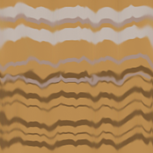

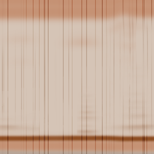

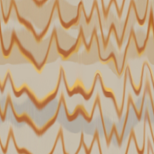

Unfortunately, the render farm has been throwing a tantrum for the greater part of this week, so I didn't get as far with blocking out my scene as I wanted to as I spent most of my time between last class and now using every computer I could to get a rough lighting render out, but I did decide to get a rough fluid simulation started for the final scene where the Keurig starts up. I know it will likely be a steep learning curve for me and wanted to give myself ample time to problem solve where trouble arises since the Keurig brewing is the last shot and probably the most important one of my project. I've also started some of the RBD simulations in the beginning. I'm generally enjoying piecing this together by starting with rough keyframes and then slowly phasing them out with the simulations as I get to each piece. As the simulations get finalized in the following classes, I will also need to adjust any UVs on models before caching them for final texture/render.